Speech therapy after thyroidectomy

Introduction

Patients who have undergone thyroidectomy often complain of changes in voice function (dysphonia) and swallow function (dysphagia) (1). Although causes of dysphonia and dysphagia may vary, one of the most common causes is recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis which can lead to vocal fold paralysis (2,3). Additionally, vocal fold paralysis often causes insufficient glottic closure which can then cause dysphonic symptoms such as, weakness, breathiness, and reduced voice range and loudness (4). Vocal fold paralysis can also cause dysphagic symptoms such as coughing, choking, and aspiration pneumonia. Because patients who have received thyroidectomy often have difficulty swallowing, another possible outcome is malnutrition (5). The various surgical interventions, for dysphonia and dysphagia are well documented and widely reported (1,2,6,7). However, non-surgical options such as speech therapy are also available for improving voice and swallowing functions. Speech therapy is a rehabilitative therapy performed by speech-language pathologists to improve communication and swallowing functions. From a therapeutic perspective, the objectives of treatment for vocal fold paralysis are restoring voice function and achieving sufficient glottic closure (8). Thus, successful therapy for vocal fold paralysis can substantially improve daily function and quality of life.

Various techniques have been developed for treating dysphonia and dysphagia caused by vocal cord paralysis (9). Some of the techniques for voice therapy and dysphagia therapy will be discussed later in this paper. Techniques for assessing voice function and swallowing function before and after speech therapy have also been developed. Regardless of the cause of vocal paralysis, the effectiveness of speech therapy for improving dysphonia and dysphagia is well documented (10,11).

Pre-therapy assessment

Some researchers suggest that patients referred for thyroidectomy should be assessed for voice and swallow function immediately before surgery (12). Most patients are assessed for baseline voice function and/or swallowing function after undergoing thyroidectomy. Pre-therapy assessment is essential for establishing the treatment goals and appropriate procedures for each patient as patients who have the same diagnosis may have different symptoms and different responses to therapy.

Voice assessment

Voice assessment can be classified into three categories: subjective assessments by the patient, subjective assessments by the clinician, and objective methods.

Subjective assessments of voice function performed by the patient include self-assessment instruments such as the Voice Handicap Index (VHI) (13) and the Voice-Related Quality of Life Measure (V-RQOL) (14). Both the VHI and the V-RQOL are used for self-assessment of the impact of voice on quality of life. Various translations of the VHI have been validated in the literature. Additionally, two versions of the VHI have been validated in previous studies: a 30-item instrument, the VHI-30 (13), and a 10-item instrument,VHI-10 (15). VHI-30 is divided into three 10-item sections for assessing physical (P) functional (F) and emotional (E) aspects of the effects of voice function on quality of life. The patients completed the VHI according to their vocal function at the time of assessment and according to the frequency at which they encountered each handicapping condition in daily life.

The 10-item V-RQOL surveys two domains, a social-emotional domain (4 items) and a physical function domain (6 items). The V-RQOL requires patients to assess their voice function in the past 2 weeks.

The second category of voice assessment methods, instruments designed for subjective assessment by clinicians, includes subjective perceptual grading scales such as the GRBAS scale (16) and the Consensus Auditory-Perceptual Evaluation of Voice (CAPE-V) (17,18).

The GRBAS scale requires the clinician to assess five parameters of voice quality (grade, roughness, breathiness, asthenia, and strain) on a scale from 0 to 3 (normal, mild severity, moderate severity, and high severity, respectively). In contrast, the CAPE-V requires the patient to perform three specific vocal tasks. The speech-language pathologist evaluates six vocal qualities: overall severity, roughness, breathiness, strain, pitch, and loudness. A 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) is then used to record and evaluate each voice quality features.

The third category of voice assessment methods is objective evaluation of acoustic voice analysis (3) and aerodynamic measurements of phonation (19).

Acoustic voice analysis has been simplified by the recent availability of speech analysis software programs for obtaining objective acoustic data for the voice. Based on voice samples such as sustained vowels or other speech sounds recorded by the patient, these software programs provide data such as fundamental frequency (F0), jitter, shimmer, noise-to-harmonic ratio (NHR), and voice turbulence index (VTI). For some patients, a voice range profile program may also be used to determine the ranges of pitch (frequency) and/or loudness (amplitude).

Objective assessment can also be performed by aerodynamic measurements of phonation, which typically include mean airflow rate, phonation threshold pressure, and air pressure. One limitation of aerodynamic measurements, however, is the specialized equipment needed for data collection. Additional voice data that are considered objective but not aerodynamic include maximum phonation time (MPT) and S/Z ratio (20).

Swallowing assessment

Swallowing function is mainly assessed by image studies and by physiologic evaluation. In some cases, swallowing function can also be assessed by quality of life questionnaires such as the 44-item Swallowing Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (SWAL-QOL) (21), which surveys ten aspects of quality of life, and the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) (22), a 10-item self-administered questionnaire used to assess symptom-specific outcomes.

The most informative image study for swallowing function is the Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study (VFSS), also known as the Modified Barium Swallow (MBS) study (9,23,24). In some cases, the fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) is also performed (25,26). The VFSS is usually administered jointly by a radiologist and a speech-language pathologist. The VFSS examination requires the patient to swallow a liquid bolus of varying consistency and/or a solid bolus of varying texture mixed/coated with barium. The swallowing process is recorded by videofluoroscopy (X-ray video). The posture and/or head position is adjusted as needed to obtain the optimal image. The VFSS enables clear observation and documentation of all stages of the swallowing process, including the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal stages. The VFSS also enables evaluation of airway integrity before, during, and after the swallow (25).

The FEES is relatively safe and easier to administer compared to VFSS (27). For example, FEES does not require exposure to radiation and is generally well tolerated by patients. The FEES can also be performed at the bedside (28). Another advantage of FEES is that the anatomy and physiology of the swallow process (26) can be recorded by fiberoptic rhinopharyngoscopy.

Physiologic methods of evaluating the swallow process (9) assess various oral and pharyngeal mechanisms such as lip closure, lingual elevation, tongue to palatal seal, bolus preparation/mastication, bolus transport/lingual motion, initiation of pharyngeal swallow, soft palate elevation and retraction, laryngeal elevation, anterior hyoid excursion, laryngeal closure, pharyngeal contraction, pharyngoesophageal segment opening, tongue base retraction, and epiglottic inversion (29). Dysphagia screening tests performed during swallow assessment may also include water swallow test (30), repetitive saliva swallow test (31) etc., or trial oral intake of liquids of varying consistency and/or solids of varying texture (9).

Voice therapy

Patients with recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis often experienced breathiness and weak voice. For these patients, the main goal of therapy is restoring sufficient voice function. Voice therapy usually requires multiple sessions and must be performed by a speech-language pathologist with expertise in voice disorders.

The many different voice therapies developed so far can be classified as direct or indirect interventions. According to a recent research, direct interventions include interventions for improving auditory, vocal, somatosensory, musculoskeletal, or respiratory function (32). Indirect interventions include, but are not limited to, vocal hygiene education and counseling.

Voice therapy orientations can also be classified as hygienic, symptomatic, and physiologic (33). Hygienic approach to voice therapy educates patients in vocal hygiene and in the need to develop good habits such as maintaining hydration and voice rest. Symptomatic approach to voice therapy resolves dysphonic symptoms such as pitch, loudness, and voice quality. Examples of symptomatic voice therapy include “chant talk”, “ear training” “head positioning”, and “pushing approach” (34). Figure 1 shows a speech-language pathologist performing head positioning on a patient. Finally physiologic approach to voice therapy, which was not proposed until the 1990s (35), and is considered the most holistic of the three approaches (36), emphasizes the need for maintaining a good balance of all systems with roles in voicing (phonation). Examples of physiologic voice therapy include “Vocal Function Exercise” (37), and “Resonant Voice Therapy” (38).

Voice therapy for patients with insufficient voicing typically include “head positioning”, “pushing approach”, “vocal function exercise” and “resonant voice therapy” (4).

Dysphagia therapy

In most parts of the world, dysphagia therapy is performed by speech-language pathologists (39). The chief complaints of patients with dysphagia are choking and difficulty swallowing. Although various interventions and behavior modifications (e.g., exercise, maneuvers, etc.) have been proposed for treating dysphagia (40,41), the most appropriate intervention depends on the specific dysphagia status of the patient.

Swallowing interventions can be classified as sensory methods (bolus modification, stimulation, biofeedback), compensatory methods (chin tuck, head rotation, head tilt, breath holding, bolus modification), motor-with-swallow methods (Mendelsohn maneuver, effortful swallow, supraglottic swallow, Masako exercise), and motor-without-swallow methods (range of motion exercise, muscle strengthening exercise, Shaker exercise, vocal exercise, breath holding) (42).

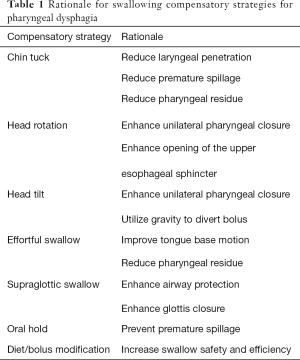

Examples of safe swallow compensatory techniques (9,23,39,43) include posture adjustments, maneuvers, bolus modifications, and sensory enhancements. Patients with vocal paralysis often experience pharyngeal dysphagia (11). Techniques for improving pharyngeal swallow include, “chin tuck”, “head rotation”, “head tilt”, “effortful swallow”, “supraglottic swallow”, “oral hold” and “diet modifications”. Table 1 shows the rationale for each technique (5).

Full table

Post-therapy assessment

The same method used to assess voice and/or swallow function before therapy should be used after therapy. The aims for post-therapy assessment are to evaluate the effectiveness of the therapy and the need for further treatment or carry-over tasks.

Special considerations for speech therapy after thyroidectomy

Apart from possible laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroidectomy, other factors must be considered when administering speech (voice and swallowing) therapy. The literature on speech-language pathology shows little or no research on the timing of voice and/or swallowing therapy after thyroidectomy. Head and neck stretching and relaxation techniques are often used in speech therapy for treating dysphonia and dysphagia (9). Before beginning speech therapy, adequate wound healing must be confirmed so as to avoid separation of the incision wound and bleeding (44). Some patients who have received thyroid surgery complain of dizziness, which may result from metabolic disturbance (44). Speech therapy should not begin until the physician addresses all complications and/or concerns.

Another important consideration is the role of strap muscle division. Laryngeal intrinsic muscles have well known roles in phonation and voicing, and laryngeal extrinsic muscles, e.g., the strap muscles, have important roles in pitch and loudness. Strap muscle division may cause dysphonia and sometimes dysphagia (45). Voice-related symptoms of strap muscle (e.g., sternohyoid) division often include hoarseness, vocal fatigue, impaired voice projection, and loss of upper range of voice pitch (45). Contraction of the sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles (strap muscles) increases pressure on the subglottis, and contracts the cricothyroid muscles. The resulting increase in vocal fold length then increases fundamental frequency (pitch) and vocal intensity (loudness) (46). Treatment for dysphonia and dysphagia related to strap muscle division include muscle relaxation techniques and muscle strengthening exercises.

Additional concerns are the same as those observed in patients who undergo endotracheal intubation under general anesthesia (45,47). Endotracheal intubation is an invasive procedure associated with a high risk of complications. For example, the intubation tube may directly irritate the mucosa of the larynx and the trachea. Mechanical injury to the mucosa is also possible (48,49). Other common complications include hemorrhage, infection, and fistula, etc. (44).

Review of current research

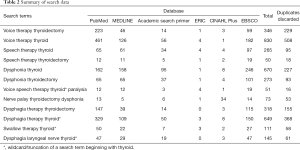

Recent studies related to speech therapy for recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroidectomy was retrieved from six databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, Academic Search Primer, ERIC, CINAHL Plus, and EBSCO. Table 2 shows that searches were limited to human studies published in 2001–2017. The search terms were “voice therapy thyroidectomy”, “voice therapy thyroid”, “speech therapy thyroid”, “speech therapy thyroidectomy”, “dysphonia thyroid”, “dysphonia thyroidectomy”, “voice speech therapy thyroid* paralysis”, “nerve palsy thyroidectomy dysphonia”, “dysphagia therapy thyroidectomy”, dysphagia therapy thyroid*”, “swallow therapy thyroid*”, and “dysphagia laryngeal nerve thyroid*”. After using Endnote X8.0.1 (50) to categorize the studies and eliminate duplicates, the first author manually screened the remaining abstracts. The review included full-text articles written in English and related to speech therapy for recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroid surgery.

Full table

After discarding duplicate studies and studies published in languages other than English, 936 articles remained. Finally, the abstracts of the 936 articles were screened for relevance. Eighteen studies discussed voice assessment and thyroid surgery with or without recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis; three studies discussed voice therapy and thyroid surgery with or without recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, and 11 studies discussed surgical interventions for voice restoration. Only three studies discussed swallowing assessment/treatment and thyroid surgery with or without recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis.

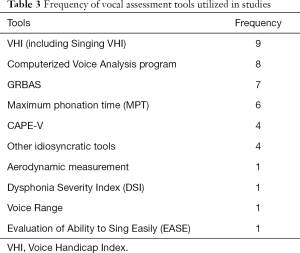

Of the 18 studies on voice assessment, VHI was used in nine (6,51-58), computerized voice analysis program was used in eight (53,54,58-63), GRBAS was used in seven (6,52,53,58,62,64,65), MPT was used in six (52,53,59,60,62,65), CAPE-V was used in four (6,55,63,66), and other non-specific idiosyncratic tools were used in four (6,61,64,67). Aerodynamic measurement (20), Dysphonia Severity Index (55), Voice Range (62), and the Evaluation of Ability to Sing Easily (51) were mentioned one time each. Table 3 shows the assessment tools and their frequency of use in the 18 papers. Notably, most studies used more than one voice assessment tool.

Full table

Of the three papers on voice therapy and thyroid surgery (1,6,68), two were literature reviews (1,6). Both reviews mentioned the option of voice therapy for improving voice outcome after thyroid surgery. One review discussed counseling and education interventions (6), and the other discussed voice outcome after voice therapy and injection laryngoplasty (68).

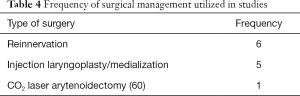

Reinnervation/nerve reconstruction (6,53,69-72) and injection laryngoplasty/vocal fold medialization (1,6,68,73,74) were the two most frequently mentioned procedures in studies that discussed surgical options for voice restoration. Table 4 shows the frequency of surgical procedures used in the 11 studies.

Full table

Three studies discussed swallow status after thyroid surgery (64,75,76). Two studies (75,76) that had been performed at the same institution had the same first authors and the same second authors. All three of the studies on swallow status after thyroid surgery discussed both voice and swallow outcomes. Swallow function was assessed by a questionnaire in two of the studies and by VFSS in one of the studies (64). Dysphagia therapy was not mentioned.

Database searches for studies published during 2001–2017 showed that changes in voice and in swallow status were common in patients who had received thyroidectomy, especially for patients who had recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroidectomy. Although many studies have discussed changes in voice and swallow functions, few have discussed the use of speech therapy for improving these functions. Additionally, studies that have discussed speech therapy for treating voice disorder (dysphonia) only briefly discuss protocols, techniques and rationales for speech therapy in these patients. Even fewer studies have discussed the use of speech therapy or other rehabilitative interventions for treating thyroidectomy patients who have dysphagia.

Conclusions

Changes in voice and swallowing functions are common complications of thyroidectomy. Although the effectiveness of speech therapy for treating dysphonia and dysphagia has been well established in the literature in recent decades, few studies have investigated the use of speech therapy for treating these disorders after thyroidectomy. A possible explanation is that surgeons, general practitioners, nurses, speech-language pathologists, and other professionals (e.g., psychologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, etc.) who treat thyroidectomy patients may not be fully aware of how thyroidectomy can impair these functions. According to the personal experience of this first author, issues related to thyroid diseases and thyroid surgery are rarely discussed in either undergraduate or graduate level courses in speech-language pathology. Therefore, the need for continuing education in thyroid disease and treatment, and increased awareness of a multidisciplinary approach to treatment is essential for all associated healthcare professionals and would be highly beneficial to these patients (6,77).

In patients who undergo thyroidectomy with recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, loss of voice and/or swallowing function are very common. Many recent studies have discussed surgical interventions for improving voice and swallowing functions in patients who suffer from recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroidectomy. Many studies have also discussed the effectiveness of speech therapy for treating dysphonia and dysphagia after vocal fold paralysis. However, few studies have specifically investigated the use of speech therapy for treating dysphonia and dysphagia in patients who suffer from recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after undergoing thyroidectomy. The use of speech therapy for treating recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroidectomy merits further study.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University (KMUH105-5R39) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 105-2314-B-037-010) Taiwan.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hartl DM, Travagli JP, Leboulleux S, et al. Clinical review: Current concepts in the management of unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroid surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:3084-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Havas T, Lowinger D, Priestley J. Unilateral vocal fold paralysis: causes, options and outcomes. Aust N Z J Surg 1999;69:509-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schindler A, Bottero A, Capaccio P, et al. Vocal improvement after voice therapy in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. J Voice 2008;22:113-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colton RH, Casper JK, Leonard RJ. Understanding Voice Problems: A Physiological Perspective for Diagnosis and Treatment (3rd Ed.). Baltimore: LWW, 2006.

- Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders (2nd edition). Austin (TX): PRO-ED 1998.

- Chandrasekhar SS, Randolph GW, Seidman MD, et al. Clinical practice guideline: improving voice outcomes after thyroid surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;148:S1-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walton C, Conway E, Blackshaw H, et al. Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis: A Systematic Review of Speech-Language Pathology Management. J Voice 2017;31:509.e7-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zealear DL, Billante CR. Neurophysiology of vocal fold paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2004;37:1-23. v. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Logemann JA. Dysphagia: evaluation and treatment. Folia Phoniatr Logop 1995;47:140-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Busto-Crespo O, Uzcanga-Lacabe M, Abad-Marco A, et al. Longitudinal Voice Outcomes After Voice Therapy in Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis. J Voice 2016;30:767.e9-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ollivere B, Duce K, Rowlands G, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis: aetiology and outcomes. J Laryngol Otol 2006;120:38-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holler T, Anderson J. Prevalence of voice & swallowing complaints in Pre-operative thyroidectomy patients: a prospective cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;43:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobson BH, Johnson A, Grywalski C, et al. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 1997;6:66-70. [Crossref]

- Hogikyan ND, Sethuraman G. Validation of an instrument to measure voice-related quality of life (V-RQOL). J Voice 1999;13:557-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, et al. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. Laryngoscope 2004;114:1549-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirano M. Clinical Examination of Voice. New York: Springer, 1981.

- Kempster GB. CAPE-V: development and future direction. Consensus Auditory Perceptual Evaluation of Voice. Perspectives on Voice & Voice Disorders 2007;17:11-3. [Crossref]

- Kempster GB, Gerratt BR, Abbott KV, et al. Consensus auditory-perceptual evaluation of voice: development of a standardized clinical protocol. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2009;18:124-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roy N, Barkmeier-Kraemer J, Eadie T, et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Voice Assessment: A Systematic Review. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2013;22:212-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon NP, Helou LB, Makashay MJ, et al. Aerodynamic evaluation of the postthyroidectomy voice. J Voice 2012;26:454-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McHorney CA, Robbins J, Lomax K, et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia 2002;17:97-114. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2008;117:919-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Logemann JA. The dysphagia diagnostic procedure as a treatment efficacy trial. Clin Commun Disord 1993;3:1-10. [PubMed]

- Guidelines for speech-language pathologists performing videofluoroscopic swallowing studies. ASHA Leader 2004;9:77-92.

- Brady S, Donzelli J. The modified barium swallow and the functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2013;46:1009-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Role of the Speech-Language Pathologist in the Performance and Interpretation of Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing: Position Statement. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2005.

- Nacci A, Ursino F, La Vela R, et al. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES): proposal for informed consent. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2008;28:206-11. [PubMed]

- Aviv JE, Kim T, Sacco RL, et al. FEESST: a new bedside endoscopic test of the motor and sensory components of swallowing. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1998;107:378-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murono S, Hamaguchi T, Yoshida H, et al. Evaluation of dysphagia at the initial diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2015;42:213-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DePippo KL, Holas MA, Reding MJ. Validation of the 3-oz water swallow test for aspiration following stroke. Arch Neurol 1992;49:1259-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hongama S, Nagao K, Toko S, et al. MI sensor-aided screening system for assessing swallowing dysfunction: application to the repetitive saliva-swallowing test. J Prosthodont Res 2012;56:53-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Stan JH, Roy N, Awan S, et al. A taxonomy of voice therapy. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2015;24:101-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas LB, Stemple JC. Voice therapy: Does science support the art? Communicative Disorders Review 2007;1:49-77.

- Boone DR, McFarlane SC, Von Berg S. The Voice and Voice Therapy (7th edition). Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2005.

- Stemple JC, Lee L, D'Amico B, et al. Efficacy of vocal function exercises as a method of improving voice production. J Voice 1994;8:271-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stemple JC. A holistic approach to voice therapy. Semin Speech Lang 2005;26:131-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stemple J. Voice Therapy: Clinical Studies. Chicago: Mosby Yearbook, 1993.

- Verdolini-Marston K, Burke MK, Lessac A, et al. Preliminary study of two methods of treatment for laryngeal nodules. J Voice 1995;9:74-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Logemann JA. The role of the speech language pathologist in the management of dysphagia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1988;21:783-8. [PubMed]

- Langmore SE, Pisegna JM. Efficacy of exercises to rehabilitate dysphagia: A critique of the literature. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2015;17:222-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal DI, Lewin JS, Eisbruch A. Prevention and treatment of dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiation for head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2636-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robbins J, Butler SG, Daniels SK, et al. Swallowing and dysphagia rehabilitation: translating principles of neural plasticity into clinically oriented evidence. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2008;51:S276-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Logemann JA. Swallowing physiology and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1988;21:613-23. [PubMed]

- Kumrow D, Dahlen R. Thyroidectomy: understanding the potential for complications. Medsurg Nurs 2002;11:228-35. [PubMed]

- Henry LR, Solomon NP, Howard R, et al. The functional impact on voice of sternothyroid muscle division during thyroidectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:2027-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong KH, Ye M, Kim YM, et al. The role of strap muscles in phonation--in vivo canine laryngeal model. J Voice 1997;11:23-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa T, Watanabe Y, Komazawa D, et al. Phonological outcome of laryngeal framework surgery by different anesthesia protocols: a single-surgeon experience. Acta Otolaryngol 2014;134:193-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paulauskiene I, Lesinskas E, Petrulionis M. The temporary effect of short-term endotracheal intubation on vocal function. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013;270:205-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moris D, Mantonakis E, Makris M, et al. Hoarseness after thyroidectomy: blame the endocrine surgeon alone? Hormones (Athens, Greece) 2014;13:5-15. [PubMed]

- Priore CF Jr, Skalski AJ, Bishop-Wright P. Networking EndNote Bibliographic Management Software for Seamless Campuswide Deployment. Computers in Libraries 2017;37:19-22.

- Randolph GW, Sritharan N, Song P, et al. Thyroidectomy in the professional singer-neural monitored surgical outcomes. Thyroid 2015;25:665-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong JW, Roh TS, Yoo HS, et al. Outcome with immediate direct anastomosis of recurrent laryngeal nerves injured during thyroidectomy. Laryngoscope 2014;124:1402-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SW, Park KN, Oh SK, et al. Long-term efficacy of primary intraoperative recurrent laryngeal nerve reinnervation in the management of thyroidectomy-related unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2014;134:1179-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Minni A, Ruoppolo G, Barbaro M, et al. Long-term (12 to 18 months) functional voice assessment to detect voice alterations after thyroidectomy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18:1704-8. [PubMed]

- Vicente DA, Solomon NP, Avital I, et al. Voice outcomes after total thyroidectomy, partial thyroidectomy, or non-neck surgery using a prospective multifactorial assessment. J Am Coll Surg 2014;219:152-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeda S, Ahmad TA, Minami S, et al. Video-assisted total thyroidectomy. Int Surg 2001;86:195-7. [PubMed]

- Solomon NP, Helou LB, Henry LR, et al. Utility of the voice handicap index as an indicator of postthyroidectomy voice dysfunction. J Voice 2013;27:348-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Pedro Netto I, Fae A, Vartanian JG, et al. Voice and vocal self-assessment after thyroidectomy. Head Neck 2006;28:1106-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Testa D, Guerra G, Landolfo PG, et al. Current therapeutic prospectives in the functional rehabilitation of vocal fold paralysis after thyroidectomy: CO2 laser aritenoidectomy. Int J Surg 2014;12 Suppl 1:S48-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeda T, Saito M, Otsuki N, et al. Voice quality after surgical treatment for thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2013;23:847-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JO, Bae JS, Chae BJ, et al. How can we screen voice problems effectively in patients undergoing thyroid surgery? Thyroid 2013;23:1437-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Na KY, Kim RM, et al. Postoperative functional voice changes after conventional open or robotic thyroidectomy: a prospective trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2963-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santosh M, Rajashekhar B. Perceptual and Acoustic Analysis of Voice in Individuals with Total Thyriodectomy: Pre-Post Surgery Comparison. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;63:32-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chun BJ, Bae JS, Chae BJ, et al. The therapeutic decision making of the unilateral vocal cord palsy after thyroidectomy using thyroidectomy-related voice questionnaire (TVQ). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015;272:727-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barczyński M, Konturek A, Stopa M, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Visualization versus Neuromonitoring of the External Branch of the Superior Laryngeal Nerve during Thyroidectomy. World J Surg 2012;36:1340-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Helou LB, Solomon NP, Henry LR, et al. The Role of Listener Experience on Consensus Auditory-Perceptual Evaluation of Voice (CAPE-V) Ratings of Postthyroidectomy Voice. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2010;19:248-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Page C, Zaatar R, Biet A, et al. Subjective voice assessment after thyroid surgery: a prospective study of 395 patients. Indian J Med Sci 2007;61:448-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jang JY, Lee G, Ahn J, et al. Early voice rehabilitation with injection laryngoplasty in patients with unilateral vocal cord palsy after thyroidectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015;272:3745-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Chen D, Chen S, et al. Laryngeal reinnervation using ansa cervicalis for thyroid surgery-related unilateral vocal fold paralysis: a long-term outcome analysis of 237 cases. PLoS One 2011;6:e19128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanuki T, Yumoto E, Minoda R, et al. The role of immediate recurrent laryngeal nerve reconstruction for thyroid cancer surgery. J Oncol 2010;2010:846235. [PubMed]

- Miyauchi A, Inoue H, Tomoda C, et al. Improvement in phonation after reconstruction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in patients with thyroid cancer invading the nerve. Surgery 2009;146:1056-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yumoto E, Sanuki T, Kumai Y. Immediate recurrent laryngeal nerve reconstruction and vocal outcome. Laryngoscope 2006;116:1657-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SW, Kim JW, Chung CH, et al. Utility of injection laryngoplasty in the management of post-thyroidectomy vocal cord paralysis. Thyroid 2010;20:513-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fang TJ, Lee LA, Wang CJ, et al. Intracordal fat assessment by 3-dimensional imaging after autologous fat injection in patients with thyroidectomy-induced unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Surgery 2009;146:82-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, De Crea C, et al. Long-term outcome of functional post-thyroidectomy voice and swallowing symptoms. Surgery 2009;146:1174-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, D'Alatri L, et al. Voice and swallowing changes after thyroidectomy in patients without inferior laryngeal nerve injuries. Surgery 2006;140:1026-32; discussion 1032-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer S, Husson O, Tomaszewska IM, et al. Quality-of-Life Priorities in Patients with Thyroid Cancer: A Multinational European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Phase I Study. Thyroid 2016;26:1605-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]