Endoscopic thyroidectomy: retroauricular approach

Introduction

Surgery remains the primary treatment for differentiated thyroid carcinoma and it is one of the treatment options for benign thyroid disease. Because differentiated thyroid carcinoma has a low mortality rate, postoperative quality of life after thyroidectomy is considered to be as important as disease control (1). The conventional method of total thyroidectomy is performed through an open transcervical incision. Recently, many efforts have been made towards the thyroidectomy technique in order to decrease the patient’s burden and morbidity. Minimally invasive surgical techniques have been developed and applied by many institutions worldwide, and more recently, numerous novel techniques of remote access surgery have been proposed and actively performed. Given that thyroid diseases predominantly affect women, the benefits of endoscopic thyroid surgery may outweigh those of conventional surgery, particularly from the cosmetic perspective (2).

Since the advent of robotic surgical systems, some have adopted the concept of remote access surgery into developing various robotic thyroidectomy techniques (3-8). The more former and widely acknowledged surgical technique of robotic thyroidectomy utilizes a transaxillary approach (TA), which was first reported by Kang et al. in South Korea (9,10). Cha et al. realized some shortcomings of robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy especially in their patients in the United States due to inadvertent, non-trivial intraoperative complications such as damage to the brachial plexus, internal jugular vein, carotid artery, and esophagus (11). They developed and reported the feasibility of robotic thyroidectomy performed via a retroauricular approach in order to overcome these potentially hazardous situations while maintaining the merits of remote access surgery (4,12). This approach avoids the less familiar territory of the axillary region and involves a shorter distance for dissection.

Herein, we introduce the surgical procedure in detail and report our experiences of retroauricular approach thyroidectomy. We also compared the impact on the postoperative function, in a prospectively enrolled cohort of patients, between endoscopic thyroidectomy via a retroauricular approach, TA and conventional open thyroidectomy.

Patient selection

For retroauricular approach endoscopic thyroidectomy, the length and circumference of the patient’s neck would be major determinants for good exposure. A patient with a short and slender neck is the best candidate for this approach, although the operation is possible on patients with thick necks. This approach can be applied in various thyroid diseases, including benign lesion of the thyroid gland needing surgery, relatively limited, small, early-stage malignant carcinomas of the thyroid, thyroid carcinomas with evident neck metastasis but without gross extracapsular spread. This indication could vary according to the surgeon’s experience. We suggest that limited application in the patient with a small-sized thyroid gland is appropriate for novice surgeons. After accumulating experiences, this approach can be performed in a patient with neck metastasis or large thyroid tumor. However, in case of gross invasion of thyroid cancer or recurrent thyroid tumor, this approach may not be safely performed.

Operative technique

Preparation of the surgical instrument

Various-sized retractor and suction tip for flap elevation, Bovie electrocautery with a long tip, and Hemoclip for ligating the vessels are needed. For endoscopic surgery, a self-retaining retractor, 30 °C endoscope, and an endoscopic ultrasonic dissector, or various endoscopic forceps are necessary for endoscopic retroauricular thyroidectomy.

Positioning of the patient and skin incision

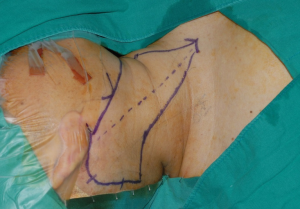

The patient is positioned supine with the head rotated to the contralateral side of the dissection. The operation can be greatly facilitated if the neck is relaxed by natural placement and not extended. Skin incision starts around the origin of the earlobe and follows along the retroauricular sulcus and the hairline. At about the level of the tragus, the incision is extended posteriorly and then curved towards the occipital direction below the hairline. The angle should not be narrow or acute to prevent skin necrosis of the flap end. Incision on the scalp is made at 0.5 cm inside of the hairline; therefore, hair shaving is needed over the area of scalp incision at 1 cm inside of the hairline (Figure 1).

Flap elevation

Flap elevation is performed at the plane superior to the fascia of the SCM muscle. Great auricular nerve and external jugular vein are preserved and left attached to the floor (Figure 2A). Flap elevation is continued inferiorly along the anterior border of the SCM muscle. Sufficient skin flap elevation is mandatory for creating an adequate working space, where the dissection area extends anteriorly to the midline of the neck to reveal the contralateral lobe of the thyroid gland and superiorly to the submandibular gland and inferiorly to the level of the sternal notch.

Exposure of the thyroid gland

The anterior border of the SCM is delineated and retracted posteriorly to reveal the carotid sheath located lateral to the ipsilateral lobe of the thyroid gland. The omohyoid muscle is identified and skeletonized. After retracting the SCM muscle posteriorly and the omohyoid muscle superiorly (Figure 2B), the exposed strap muscles is also dissected at the lateral side and maintained superiorly by the retractor to reveal the superior pole of the thyroid gland (Figure 2C). Once the contour of the thyroid gland is fully exposed and a sufficient working space is established, a self-retaining retractor is applied (Figure 3).

Preparing for the endoscopic surgery

After applying the self-retraining retractor, an assistant holds the right angled retractor to retract the SCM muscle to the lateral side. Another assistant holds the 30 degree endoscope at the superior side, and the main operator stands toward the inferior side.

Dissection of the superior pole

While holding the superior pole by endoscopic forceps and pulling it laterally, the superior thyroid artery and vein are ligated using ultrasonic devices. With retraction of the superior pole of the thyroid, dissection is continued to the medial side by separating the thyroid from the cricothyroid muscle (Figure 4A). After detaching the superior pole from the cricothyroid muscle, dissection of the posterolateral area of the thyroid gland is performed by retracting the thyroid to the anteromedial side. Caution is exercised so as not to injure the recurrent laryngeal nerve at the level below the cricoid cartilage. Superior parathyroid is easily identified during the dissection and is preserved.

Identification of the lower pole and recurrent laryngeal nerve

After retracting the whole thyroid gland to the medial side, capsular dissection at the lateral side is performed. Careful dissection with an ultrasonic device and blunt dissection is needed so as not to injure the recurrent laryngeal nerve. More caution is exercised while dissecting the area just below the superior pole where the recurrent laryngeal nerve is right below the thyroid gland. In addition, because medial traction of the thyroid gland causes retraction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the medial side, the surgeon should keep in mind that the nerve is usually identified in the more upper area than expected (Figure 4B). Inferior parathyroid is identified and detached from the thyroid gland.

Dissection of Berry’s ligament and isthmectomy

After dissection of the thyroid from the recurrent laryngeal nerve, the thyroid gland is detached from the trachea and Berry’s ligament (Figure 4C). At the midline, isthmectomy is performed and the specimen is taken out.

Hemostasis and drain insertion

After removal of the final specimen, the surgical bed is irrigated with warm saline and thorough observation and meticulous bleeding control are performed under endoscopic visualization. A closed suction drain is placed in the surgical bed and it is inserted behind the hairline, and skin wound closure is performed with simple, interrupted sutures.

Postoperative care

Postoperative management is no different from that after conventional total thyroidectomy. The neck should be closely monitored for any signs of hemorrhage, hematoma, seroma, or subcutaneous emphysema. According to our experience, the average amount of blood loss during uncomplicated total thyroidectomy is minimal, not exceeding 10 mL. The closed suction drain, Hemovac should be removed when the drainage amount falls to less than 20 mL per day. In our experience, the wound drainage catheter can be removed within maximum 4 days. Any local signs of skin discoloration or skin flap necrosis should be routinely checked. The patient can be discharged within about 4 days after the operation, one day after the suction drain has been removed.

Complications

Some possible postoperative complications are listed below. These complications are no different from those of the conventional type of surgery, and in our experience, we have not encountered any case of major permanent vocal cord paralysis and have encountered limited number of hypoparathyroidism cases which were managed conservatively. The incidences of temporary mouth corner deviation from indirect injury to the marginal mandibular nerve and transient ear lobe numbness from indirect injury to the greater auricular nerve are low. All cases are conservatively managed and closely observed, and in the end these conditions normalize after several months. Acute postoperative hemorrhage or hematoma occurs rarely, mostly from minor vessels within the skin flap. There is a rare chance of large-volume acute bleeding when concomitant neck dissection has been performed. However in most situations, the problem can be resolved locally and conservatively. Despite these occasional, minor complications, the patient who has undergone this operation can achieve an excellent cosmetic result and may not suffer from possible lymphedema that occurs after radical neck dissection.

Possible postoperative complications after retroauricular thyroidectomy are as follows: (I) nerve injury (recurrent laryngeal nerve, superior laryngeal nerve, marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, and great auricular nerve); (II) hypoparathyroidism; (III) seroma/hematoma/hemorrhage; (IV) wound-related problems (hair loss along the incision line, wound infection, dehiscence, skin flap necrosis, discoloration, hypertrophic scar, keloid formation).

Surgical outcomes and functional outcomes

We recently performed two prospective studies of retroauricular approach thyroidectomy. One study has been published, which showed that endoscopic thyroidectomy via the retroauricular approach is a safe, feasible, and cosmetically desirable treatment option with outcomes comparable to conventional open thyroidectomy (13). From May 2013 to December 2013, this study included 47 patients who underwent endoscopic hemithyroidectomy via the retroauricular approach and the same number of controls who underwent conventional hemithyroidectomy. The groups were compared using the χ2 test, the Mann-Whitney U test, the student’s t test, or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative or quantitative variables, as appropriate using the SPSS statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. In this study, none of the cases had to be converted to open approaches. The mean total operative time was 152±48 minutes, with a mean flap creation time of 75±24 minutes. The mean endoscopic procedure time was 58±18 minutes. The operative time was longer in the patients who underwent retroauricular thyroidectomy than in controls (65.21±26.86 minutes in the open surgery group; P<0.001). In terms of postoperative complications, no differences were observed between the two groups (temporary vocal fold paralysis, P=1.0 and postoperative hematoma, P=0.242). There were no inadvertent injuries to the trachea, esophagus, or larynx during any of the operations in both groups.

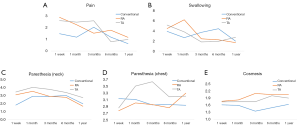

Although most of the parameters for the functional outcome were worse in the patients who underwent surgery via the retroauricular approach, these differences were transient. Subjective worsening of the voice handicap index and dysphagia handicap index normalized by 3 months postoperatively. The average pain score on a visual analogue scale at 1 week after surgery was 2.84, representing a tolerable range of discomfort. The mean paresthesia/hyperesthesia score was worse in the patients who underwent retroauricular thyroidectomy than in the open surgery group by the postoperative month 6. However, these differences eventually disappeared. Thirty-six of the 47 patients in the ETE group were satisfied or extremely satisfied with the retroauricular incision by 6 months after surgery (Figure 5).

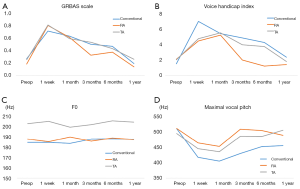

We performed an additional study to compare the surgical and functional outcomes after retroauricular hemithyroidectomy via the TA and conventional hemithyroidectomy. From May 2011 through December 2013, 153 patients who underwent hemithyroidectomy were prospectively categorized into three groups according to the surgical approach used (retroauricular approach, TA, and conventional hemithyroidectomy groups). All patients underwent prospective acoustic and functional evaluation, using a comprehensive battery of functional assessments, preoperatively and postoperatively at 1 week, 1 month, 3, 6, and 12 months. Results are presented as the mean value ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as counts and group percentages for categorical variables. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using paired t-tests for comparisons between two groups and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons among three or more groups. Dichotomous outcomes were analysed using the chi-square test for trend.

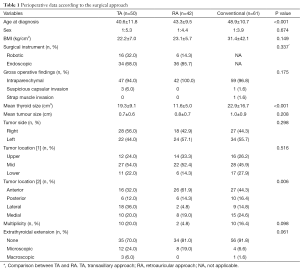

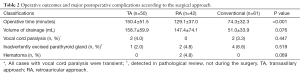

In this study, age at diagnosis was significantly lower in the retroauricular approach (n=42) and TA (n=50) groups than in the conventional group (n=61) (P<0.001) (Table 1). The frequency of occurrence of vocal cord paralysis, inadvertently excised parathyroid, and hematoma did not differ among the groups (P=0.447, 0.519, and 0.069, respectively) (Table 2). Three months postoperatively, maximal vocal pitch was significantly higher in the retroauricular group than in the conventional and transaxillary groups (P=0.021) (Figure 6). Although the overall pain score was not different, the dysphagia handicap index in the retroauricular group at 1 month postoperatively was significantly higher (P<0.001) than that in the other groups. Chest paresthesia was significantly more severe in the transaxillary group, especially at 3 months postoperatively (P=0.035). The cosmetic satisfaction score was significantly higher in the retroauricular group and transaxillary group than in the conventional group (P=0.001 and 0.035, respectively) at 3 and 6 months postoperatively (Figure 7). Therefore, this study demonstrated that both retroauricular hemithyroidectomy were associated with excellent surgical outcomes, especially in terms of cosmesis; however, delayed recovery of swallowing with the retroauricular approach may be a worrisome factor.

Full table

Full table

Conclusions

The benefits of retroauricular approach over the other better-known endoscopic approaches such as the TA, and bilateral axillo-breast approach (BABA) are as follows: (I) the working distance to the thyroid gland is shorter. A smaller area of dissection compared to other endoscopic approaches will result in less tissue trauma. In a cadaveric study, the area of dissection required to accomplish a transaxillary thyroidectomy was 38% greater than that necessary for a retroauricular approach (12); (II) the operation would be more comfortable due to familiar local anatomical structures, easier to address level VI lymph nodes along the RLN compared with the TA approach; (III) the risk of intraoperative great vessel injury would also be avoided (Table 3).

Full table

Although retroauricular approach is technically feasible and safe intraoperatively and has comparable surgical outcomes, the oncologic safety of the procedure for thyroid cancer needs to be established. The major limitation of this approach is that a bilateral retroauricular approach is necessary when total thyroidectomy is indicated.

In our study, retroauricular approach was found to be superior to conventional open thyroidectomy in terms of the excellent cosmetic outcome and is comparable to, or at least not inferior to, that of conventional open thyroidectomy in a prospective 1-year comparative functional study. However, a longer operative time was observed with TA thyroidectomy and RA thyroidectomy. Surgeons should keep in mind that longer operation times and the associated postoperative morbidity may be inevitable even in the hands of an experienced surgeon. Moreover, the procedures in this study were performed by a high-volume surgeon (performing over 200 cases of conventional thyroidectomy and over 150 cases of extra-cervical thyroidectomy per year). Were the studies to be performed by low-volume surgeon(s)? The result could be totally different with adverse patient complaints becoming a more prominent feature of the study.

Although the overall complication rate was approximately equal in all groups, parathyroid identification and preservation tended to be better with TA thyroidectomy and RA thyroidectomy than with conventional open thyroidectomy, which in a further study with a larger cohort, could result in a lower complication rate. Both TA thyroidectomy and RA thyroidectomy were associated with better postoperative functional outcomes, including voice and cosmetic outcomes. Recovery of maximal vocal pitch was best with RA thyroidectomy, while swallowing outcomes were better with TA thyroidectomy than with the other approaches. Longer operative times with TA thyroidectomy and RA thyroidectomy, delayed recovery of swallowing with RA thyroidectomy are the issues that remain to be overcome. A further prospective study with a larger cohort is needed to elucidate the surgical outcomes (including the complication rate) and the role of robotic systems in RA thyroidectomy.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ryu J, Ryu YM, Jung YS, et al. Extent of thyroidectomy affects vocal and throat functions: a prospective observational study of lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy. Surgery 2013;154:611-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimizu K, Tanaka S. Asian perspective on endoscopic thyroidectomy -- a review of 193 cases. Asian J Surg 2003;26:92-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Feng Z, Li J, et al. Endoscopic thyroidectomy via areola approach: summary of 1,250 cases in a single institution. Surg Endosc 2015;29:192-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer MC, Seybt MW, Terris DJ. Robotic facelift thyroidectomy: I. Preclinical simulation and morphometric assessment. Laryngoscope 2011;121:1631-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Na KY, Kim RM, et al. Postoperative functional voice changes after conventional open or robotic thyroidectomy: a prospective trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2963-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal S, Sabaretnam M, Ritesh A, et al. Feasibility and safety of a new robotic thyroidectomy through a gasless, transaxillary single-incision approach. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:1097; author reply 1097-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryu HR, Kang SW, Lee SH, et al. Feasibility and safety of a new robotic thyroidectomy through a gasless, transaxillary single-incision approach. J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:e13-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terris DJ, Singer MC, Seybt MW. Robotic facelift thyroidectomy: patient selection and technical considerations. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011;21:237-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee S, Ryu HR, Park JH, et al. Excellence in robotic thyroid surgery: a comparative study of robot-assisted versus conventional endoscopic thyroidectomy in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients. Ann Surg 2011;253:1060-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Nam KH, et al. Robot-assisted endoscopic thyroidectomy for thyroid malignancies using a gasless transaxillary approach. J Am Coll Surg 2009;209:e1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cha W, Kong IG, Kim H, et al. Desmoid tumor arising from omohyoid muscle: The first report for unusual complication after transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy. Head Neck 2014;36:E48-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terris DJ, Singer MC, Seybt MW. Robotic facelift thyroidectomy: II. Clinical feasibility and safety. Laryngoscope 2011;121:1636-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung EJ, Park MW, Cho JG, et al. A Prospective 1-Year Comparative Study of Endoscopic Thyroidectomy via a Retroauricular Approach Versus Conventional Open Thyroidectomy at a Single Institution. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3014-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]